Ecological Disasters

Industrial disasters around the world, many involving multinational corporations, have caused significant health, environmental, and economic damages. Such tragedies have also led to lengthy legal challenges and prompted new global regulations.

Japan’s ‘Four Big Pollution Diseases’

Decades of mishandling industrial waste in Japan lead to repeated outbreaks of serious diseases, beginning in 1912 with reports of Itai-itai disease, a painful skin and bone condition. Mitsui Mining & Smelting Company faces blame for dumping cadmium in the Jinzu River. Two versions of Minamata disease, which can lead to paralysis and death, break out in 1956 and 1965 after the Chisso Corporation and Showa Denko K.K. dump methylmercury into local water supplies. Yokkaichi asthma emerges in 1956, and blame falls on Yokkaichi Kombinato’s petrochemical processing facilities and refineries. In 1971 and 1973, district courts find Chisso and Showa Denko fully responsible [PDF] for Minamata disease, awarding victims millions of dollars in damages. Similar rulings follow for the other ailments, though health issues from the diseases and related legal battles continue. Japan’s experience influences many nations to set new limits on industrial pollutants, including through the Minamata Convention on Mercury, an international treaty that eventually gains 128 signatories.

Niger Delta Oil Pollution

An estimated nine to thirteen million barrels of oil [PDF] are spilled in the Niger Delta over fifty years since commercial oil production begins there in 1958, mainly from oil operations jointly owned by Shell and the Nigerian government, making the delta one of the most polluted areas in the world. Civil unrest flares over how the government distributes oil wealth; and there are incidents of militants kidnapping and killing oil workers, blowing up pipelines, and stealing oil. Nigeria also faces unrest over extensive damage to fisheries as well as water and soil quality. In 2008, four Nigerian farmers file a lawsuit in a Dutch court against Shell, but the court dismisses most claims. Shell says only a small percentage of the spills are from operations failures and that most are caused by sabotage and theft stemming from the country’s internal conflict. In 2009, the company settles a lawsuit accusing it of colluding with the government in the 1995 executions of six activists but it admits no wrongdoing.

Ecuador’s Amazon Degradation

More than four hundred million barrels of toxic oil waste are released into watersheds from oil operations in the Amazon Rainforest over nearly thirty years, which the indigenous community contends causes widespread health problems. Indigenous communities sue for damages for cleanup in U.S. courts, but the case later moves to courts in Ecuador at Chevron’s request. Chevron argues Petroecuador, the state-owned oil firm it partnered with during that time period, is responsible for the environmental damage, and it files an international arbitration suit at The Hague against the Ecuadorian government for trying to avoid contractual responsibilities. In February 2011, Ecuador’s Supreme Court orders Chevron to pay $8.6 billion in damages, plus another $9 billion if the company does not apologize. But Chevron challenges the ruling. In 2018, a tribunal administered by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague rules in favor of Chevron, stating that the 2011 Supreme Court ruling was the result of fraud, bribery, and corruption. The court is still determining damages suffered by Chevron.

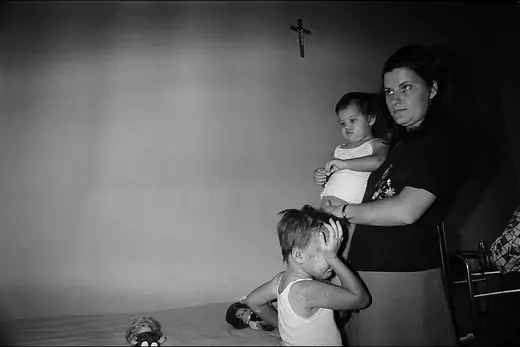

Peru’s Amazon Degradation

An estimated nine billion barrels of oil wastewater is released into Amazonian watersheds, which members of Peru’s indigenous Achuar community say has caused unexplained diseases, tumors, skin ailments, and miscarriages from oil exposure. In 2007, the Achuar community sues U.S.-based Occidental Petroleum in U.S. courts for environmental and health damages caused by the pollution. Plaintiffs allege that the company ignored industry standards and violated U.S., Peruvian, and international law. Occidental says there is no evidence of detrimental health effects. In 2015, the two sides reach a settlement outside of court, the size of which has not been made public.

Papua New Guinea’s Panguna Mine War

The residents of Bougainville Island allege large-scale environmental destruction from global mining conglomerate Rio Tinto’s Panguna copper mine, one of the world’s largest open-pit mines. After the mine is opened in 1972, about one billion tons of mining waste containing sulfur, arsenic, copper, zinc, cadmium, and mercury is dumped into the local river system, rendering a forty-mile portion of the system biologically dead, according to environmental activists. The situation gives rise in 1989 to a decade-long revolt by residents of Bougainville against the government over unanswered grievances. In 2000, island residents sue Rio Tinto in U.S. federal court under the Alien Tort Claims Act, which allows claims against companies that violate international law. Rio Tinto calls the suit’s allegations false and defamatory. The mine remains closed, but Bougainville’s government has signaled that it could be revived.

Italy’s Seveso Dioxin Cloud

A dioxin cloud from an accident at a chemical plant near Seveso, Italy, sickens at least two thousand people and causes eighty thousand animals to be slaughtered to keep the poison from entering the food chain. Five employees of the plant, a local subsidiary of Swiss cosmetics manufacturer Givaudan, are criminally prosecuted and convicted, and the company is required to pay 20 billion lire (roughly $13 million) in compensation following a settlement in 1980. The accident also prompts Europe to adopt the Seveso Directive in 1982, which regulates the manufacture and storage of hazardous materials.

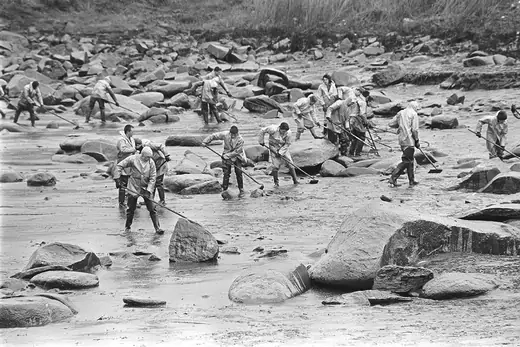

France’s Amoco Cadiz Tanker Spill

An Amoco tanker spills an estimated two million barrels of oil off the coast of France, polluting approximately two hundred miles of coastline and harming wildlife. The disaster occurs just one month after a meeting of the signatories of International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) that was aimed at expanding safety requirements for tankers to reduce the likelihood of pollution. In response to a suit brought by the French government, businesses, and private citizens, a U.S. district court orders Amoco to pay $200 million in cleanup costs and damages to the French government and towns. Enough countries ratify the MARPOL convention in 1982 and the new international rules for tankers go into force a year later, though it is unclear what effect the incident has on ratification.

India’s Bhopal Cyanide Gas Leak

The leak of methyl isocyanate gas from a chemical plant operated by U.S. company Union Carbide in Bhopal, India, kills at least four thousand people, sickens an estimated half million people, and leaves survivors with numerous health ailments, including blindness, chronic respiratory trouble, and birth defects. The Indian government accepts a settlement of about $470 million from Union Carbide in 1989 that victims say is inadequate. New Delhi seeks the extradition of the company’s CEO from the United States for criminal prosecution, but Washington refuses and he never returns and dies in 2014. Victims continue to fight for compensation. Following the incident, the Indian government passes laws to address industrial accidents, including the 1986 Environment Protection Act and the 1991 Public Liability Insurance Act.

Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster

A reactor explosion at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Soviet Ukraine in 1986—coming seven years after a partial meltdown at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island nuclear facility—clouds the future of nuclear power around the world. Chernobyl’s disaster kills thirty-one people directly, though estimates of its long-term death toll vary widely, from the World Health Organization’s estimate of five thousand deaths to Greenpeace’s of ninety thousand. In response, more than 110 countries sign the Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident, a treaty requiring notification of any potential cross-border nuclear accidents. Nuclear development slows in many places: the United States fails to approve a new nuclear power plant until 2012, and some European countries—notably Denmark, Italy, Sweden, and Germany—implement nuclear bans or otherwise plan to phase out nuclear power.

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill

The Exxon Shipping Company–owned Exxon Valdez oil tanker spills 10.8 million gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound, off the Alaskan coast, after striking a reef. The spill pollutes 1,300 miles of coastline, killing 250,000 seabirds, 3,000 sea otters, and 250 bald eagles, and destroys billions of salmon eggs in a major blow to Alaska’s fishing industry. In response to global concern, the U.S. Congress passes new legislation to regulate the shipping industry, including the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, which increases penalties for oil spills, sets requirements for vessel construction, and mandates that all tankers operating in U.S. waters be double-hulled. In addition, a 1992 amendment to the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution From Ships (MARPOL), which has over 155 signatories in 2021, requires that all newly built tankers be double-hulled.

Romania’s Cyanide Spill

The Baia Mare gold mine in Romania spills more than thirty-four million gallons of cyanide into the Lupes, Somes, Tisza, and Danube Rivers. The spill decimates aquatic and plant life for dozens of miles, affecting local fishing industries and impeding access to drinking water for residents of Serbia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria for several months. In 2001, Hungary sues the mining company, a joint Australian-Romanian venture named Aurul, for roughly $200 million in damages to fisheries. A few months after the incident, mining resumes, but in 2005 a European Union judge bans mining on 85 percent of the site pending further investigation. Efforts to ban the use of cyanide in mining in Romania are repeatedly blocked. In 2010, the European Parliament proposes banning cyanide use in mining across the EU, but the ban is never implemented [PDF] by the European Commission.

Ivory Coast’s Toxic Waste Dumping

Dutch oil trader Trafigura transports four hundred tons of toxic waste consisting of caustic soda and petroleum residue from Amsterdam to Abidjan, dumping it into the Ivorian city’s waste system. The deaths of seventeen people and illnesses of as many as one hundred thousand people are linked to the waste dumping. Trafigura admits no wrongdoing [PDF] and blames a subcontractor for the incident. In 2007, the company agrees to pay about $195 million to the Ivorian government for cleanup and compensation for victims. In 2009, it pays another $45 million to thirty thousand victims who sued the company in a British court, but it continues to deny any wrongdoing.

Deepwater Oil Spill

An explosion on a BP oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico, which was drilling in underwater depths of more than one mile, kills eleven people and causes the largest oil spill in U.S. history, estimated at nearly five million barrels. U.S. officials struggle to contain the spill, which lasts nearly three months, and the disaster causes an estimated $17.2 billion in damage to beaches, wildlife, fisheries, and tourism. The administration of U.S. President Barack Obama pressures BP into establishing a $20 billion fund to pay for damages and cleanup. It also places a six-month ban on deepwater oil drilling and creates a commission to study the spill. Following the commission’s recommendations, the administration imposes new regulations on drilling, though many of these are later removed under the Donald J. Trump administration.

Amazon Wildfires

Record wildfires in Brazil’s Amazon Rainforest highlight growing concerns over deforestation and development of the Amazon. Fires there are often intentionally set for agricultural purposes but sometimes escape their intended boundaries. The wildfires in 2019 and 2020 are particularly intense, with over eighty thousand fires reported and more than three million hectares burned, an area larger than the state of Massachusetts. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who critics say has allowed increased deforestation, initially refuses global aid but later accepts $12 million from the United Kingdom. Many experts blame the beef and soy industries for much of the deforestation; some estimates show cattle ranching is responsible for up to 80 percent of rainforest loss. Brazilian conglomerate JBS S.A., the largest meat processor in the world, pledges to improve its cattle-purchasing practices after investigations link some of its suppliers to illegal deforestation.

Online Store

Online Store